About my Tatar village

Shamil Khairov

A Tatar village in Mordovia

I was born in a Russian city and grew up bilingual in a Tatar-speaking family. Though I cannot call it my native village, it is my parents' and ancestors' native place. I spent many summer months of my childhood there, staying with my grandparents in their small wooden house at the very end of the street during school vacations. Now, living far away—both in time and distance—I often return in my memories to those modest people who lived in a tiny Tatar enclave within the vast ocean of the Soviet Empire.

There are about six million Tatars worldwide, with roughly half residing in Tatarstan, a national autonomy in Russia’s Volga region. My Tatars, however, do not live in Tatarstan but close by—just a dozen miles from Saransk, the capital of the Mordovian Autonomous Republic where Mordvins make up 40% of the population, Russians 53%, and Tatars 5.2%.

Tatars appeared in the territory of Mordovia in the 14th –16th centuries. The first settlements were associated with the Golden Horde and the Kazan Khanate. After the conquest of Kazan by Ivan the Terrible in 1552, more Tatars migrated to Mordovia. The Tatar population grew steadily throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, as the Russian government actively recruited Tatars to guard the empire’s borders. Among them were murzas and princes whose lands were exempt from taxes. According to archival records, our village was founded in 1642, and since then, its history has become intertwined with Russia’s—typical of many national minorities within the Russian Empire.

Separated from Russians by religion and language, the village remained monoethnic (Sunni Muslim) and monolingual until 1980-s. While the villagers could communicate in Russian, true bilingualism was rare. My father was one of the few who spoke both languages fluently. This was a result of collectivisation in Mordovia. In 1930, when villagers were forced to join a kolkhoz, surrendering their livestock and farming tools to the collective—essentially to the state—my grandfather, a skilled and independent peasant, refused. Instead, he took his horse and, along with his wife and their young son (my father), left for Nizhny Novgorod to work at a large industrial buidling site. They spent several years moving from one construction site to another but eventually had to return and join the collective farm. In 1941, both my grandfather and father went to war, returning in 1945 wounded. During World War II, my mother worked as a tractor driver in the village kolkhoz.

Tatar is a Turkic language. Until the late 1920s, Tatars in Russia used the Arabic alphabet, which was later replaced by the Latin and subsequently by the Cyrillic alphabet. Our family still has a letter written by one of our parents in the Latin script.

My parents married a few years after the war and, like millions of their generation across the USSR, moved to the nearest city in search of a better life. For many villagers, this transition to city life was difficult and often traumatic due to their poor Russian. They seized every opportunity to return to the countryside on weekends and holidays—only there did they truly flourish and feel a deep sense of belonging.

The new city dwellers at a wedding in their native village: early 1950-s.

The post-war exodus to the cities resulted in a new generation of bilingual Tatars who spoke Tatar with their now working-class parents, and Russian at school and outside home. Tatars were not alone to experience this transformation in Mordovia – the same story was typical for Mordvins who, while being Orthodox Christians retaining a solid Pagan component – did not speak good Russian: their language belongs to Uralic language group and shows many similarities with Finnish or Estonian. Our wooden house in Saransk hidden in the backyard of a monumental building erected in Stalin times consisted of 14 flats, with no central heating and running water, but with a beautiful garden around it, was quite multinational: our neighbors were Russians, Mordvins, and Jews. To invite neighbors to celebrate family events or state holidays was a common thing.

Three ethnicities at one table: two Russian ladies smiling and raising their glass of brazhka, an alcoholic drink made of yeast and bread, a Mordvin playing the accordion, and my grandfather wearing a kepetch, a traditional Tatar hat. 1950s. My mother and sister stand on the left. The picture was taken by my father. I had not been born yet.

Up until the 1980s, Tatar was the only language spoken in the village. Tatars married only Tatars, though two our distant female relatives married an Uzbek and a Tajik and moved to their distant republics. Until 1980, there was only one mixed Tatar-Russian marriage in the village.

However, due to mass migration from the countryside to big cities during the Soviet period, the children of working migrants grew up in Russian-speaking environments, becoming bilingual and often losing their Tatar language—and with it, their cultural identity. City-born children of former villagers were largely non-religious and more often married non-Tatars. Their children were exposed to the Tatar language only in the village.

In the 1990s, and especially in the 2000s, the children of the first wave of internal migrants began resettling in the village—some permanently after retirement, others only for the summer. This, along with urban expansion, the influence of mass media, and the internet, led to the partial Russification of the village. Today, the language of instruction in the local school is Russian.

I visited the village several times in 1990-s and 2000-s and managed to take pictiures and record some fascinating stories from my elderly aunties about their life in 1940-s and 1950-s. Only one of them is living at moment of writing these lines. The influence of the big city is visible. There is an agricultural production in the village but a great number of the villages now commute to work in the city. The village is squeezed between two motorways which made commuting much easier but also resulted in the loss of the natural environment. The river where I used to go fishing is now on the other side of the motorway.

Lunch in the garden.

The new motorway cuts off the village from the river and meadows.

The remnants of the kolkhoz.

Tatars value community and tradition. They show deep respect for the elderly, often hosting prayer services at home and inviting them for special meals. At the same time, the middle-aged generation does not shy away from alcohol and enjoys singing both Tatar and Russian songs—though only when the elders are not present.

Modern times: respecting the elderly, 2010.

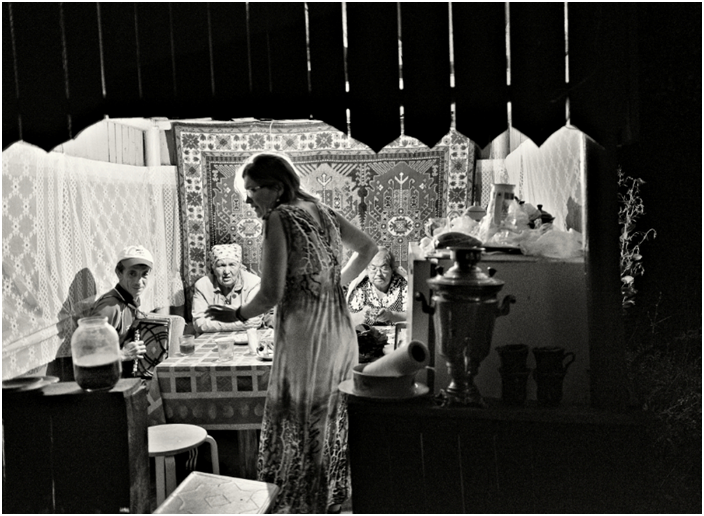

Women live much longer in the village: most of the guests here are widows.

A warm farewell

Returning home

Small pleasures of singing and dancing in the open air.